Gustave Doré and the Vision of the Celestial Rose: Paradiso Canto 31 Illuminated

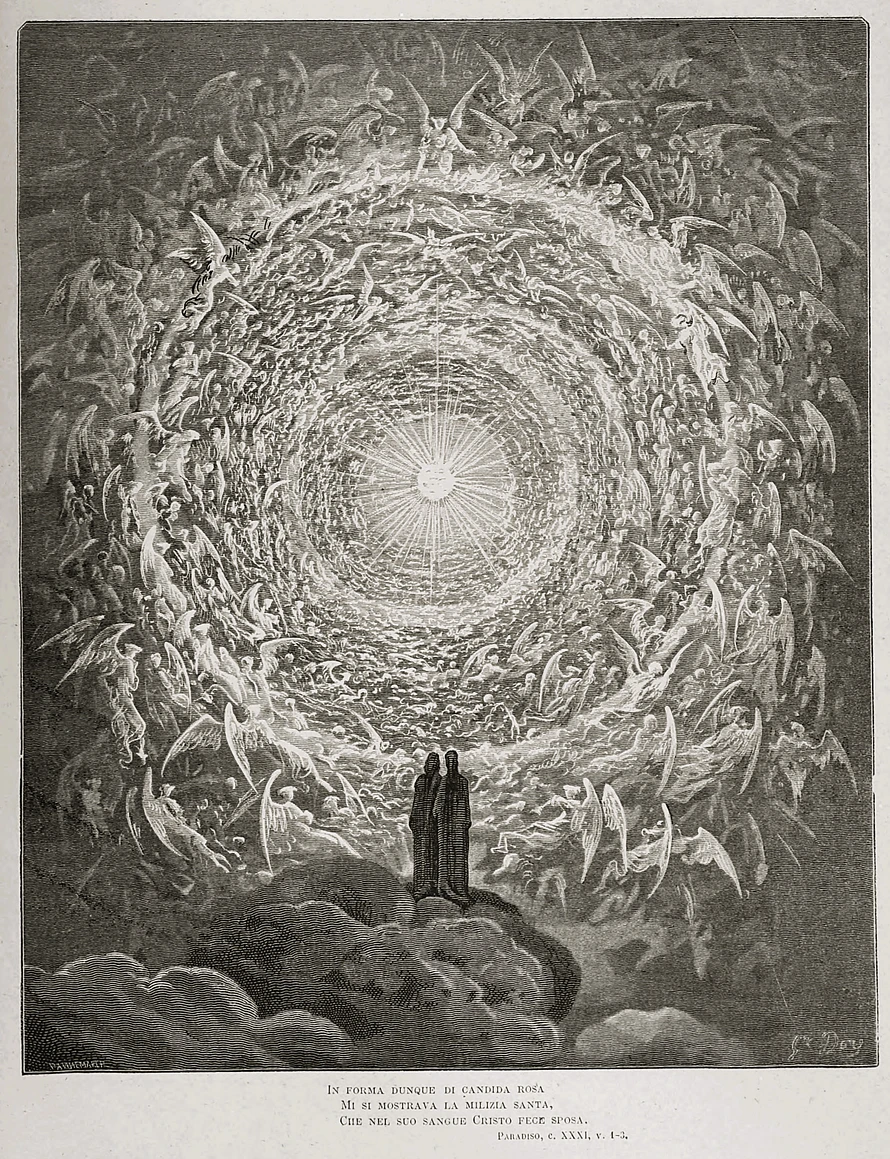

Few illustrators have matched the visionary brilliance of Gustave Doré, the 19th-century French artist whose engravings brought new life to the great literary works of the Western canon. Among his most iconic illustrations are those for Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, a series that stands as a pinnacle of visual interpretation. In Paradiso Canto 31—one of the most mystical and abstract cantos—Doré faced the enormous challenge of depicting the Empyrean, the highest heaven, and the Celestial Rose, a symbolic vision of divine love and unity.

The Celestial Rose in Dante’s Paradiso

Paradiso Canto 31 is a culmination of Dante’s spiritual ascent. After journeying through the spheres of Heaven with Beatrice as his guide, he arrives at the Empyrean—a realm beyond space and time, illuminated by the pure light of God. Here, Dante sees the Celestial Rose, or Rosa Celeste, a vast amphitheater of radiant souls arranged in the shape of a white rose. Each petal represents a saved soul, glowing with divine grace and resting in eternal contemplation of the divine.

The rose is not merely a poetic symbol; it’s Dante’s way of expressing the ineffable order and beauty of the beatific vision. At the center of this celestial architecture sits the Virgin Mary, encircled by angels, while the petals fill with patriarchs, apostles, martyrs, and saints—all in their rightful places.

Gustave Doré’s Interpretation

Doré’s engraving of this scene captures the overwhelming vastness and spiritual intensity of Dante’s vision. Rather than attempt to portray individual faces in the multitude, Doré emphasizes the architectural grandeur of the rose. Rows upon rows of figures curve upward into a heavenly dome, like the interior of a gothic cathedral made of light.

What makes Doré’s work so effective is his ability to evoke the sublime. The figures, though small and indistinct, radiate serenity and order. The light streaming from the center—suggesting the presence of God—draws the eye inward, echoing Dante’s final realization that divine love moves the sun and the other stars.

Artistry and Spirituality Intertwined

Doré’s engraving does more than illustrate; it interprets. He faced the challenge of translating Dante’s profoundly metaphysical poetry into something tangible. Rather than reducing the divine mystery to human scale, Doré expanded human imagination to grasp the divine. His use of contrast—light and shadow, the ethereal and the earthly—mirrors Dante’s own poetic movement from the material to the spiritual.

Why It Still Resonates

In a time when much of religious art sought either strict realism or sentimental moralism, Doré’s engraving stands apart. It doesn’t preach; it invites. It doesn’t explain; it reveals. His Celestial Rose remains a powerful visualization of divine harmony, and a testament to both Dante’s poetic genius and Doré’s artistic vision.

Whether you are a lover of literature, a student of theology, or simply an admirer of great art, Gustave Doré’s depiction of Paradiso Canto 31 offers a moment of wonder—a glimpse into the unseeable, made visible through lines and light.